Brian Marick's 1999 paper, "New Models for Test Development ![]() " critiqued the so-called "V model

" critiqued the so-called "V model ![]() " for test development. The strategy was similar to Royce's Diagrams𓅮 and had a similar result.

" for test development. The strategy was similar to Royce's Diagrams𓅮 and had a similar result.

This page is an Example.

the figures

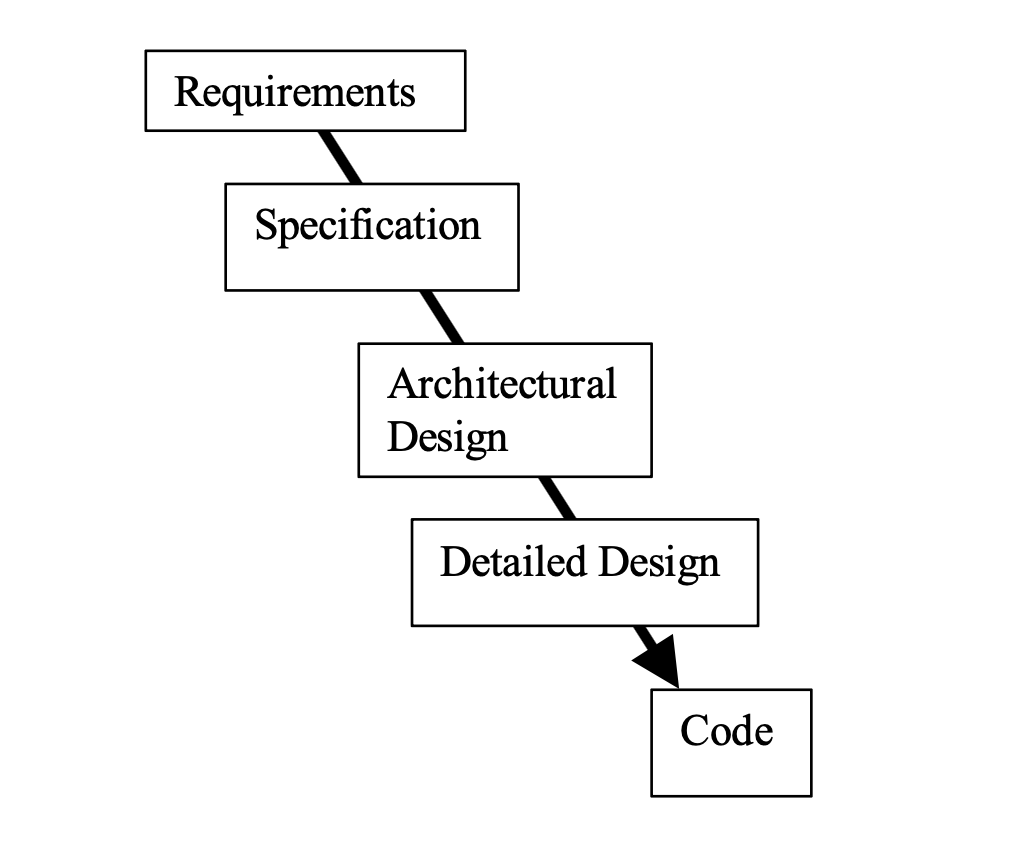

The V model starts from the waterfall model.

> "That’s the age-old waterfall model. As a development model, it has a lot of problems. Those don’t concern us here – although it is indicative of the state of testing models that a development model so widely disparaged is the basis for our most common testing model."

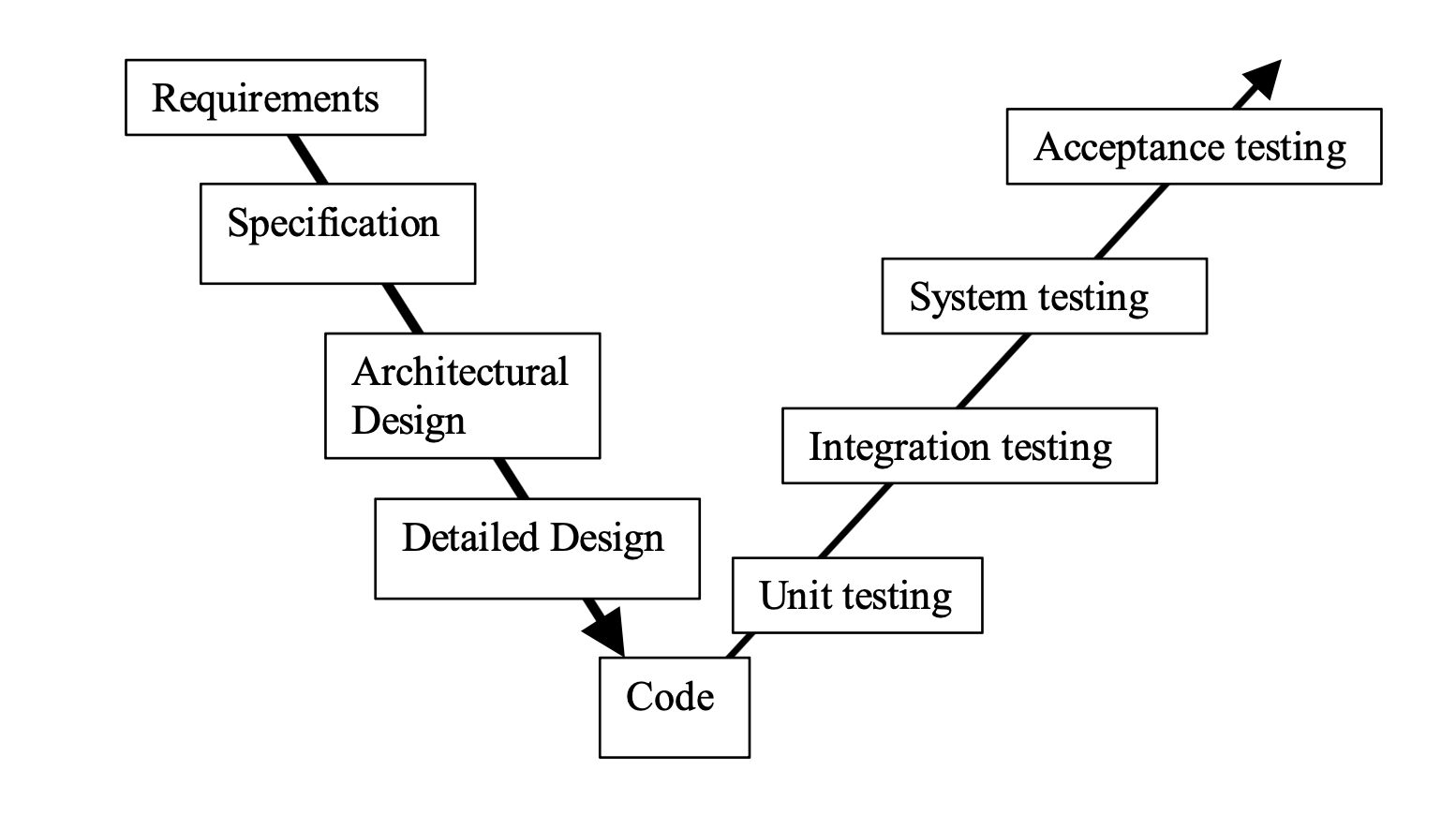

The V model ties a particular kind (and phase) of testing to waterfall-model phases. Note the pleasing symmetry.

> Unit testing checks whether code meets the detailed design. Integration testing checks whether previously tested components fit together. System testing checks if the fully integrated product meets the specification. And acceptance testing checks whether the product meets the final user requirements.

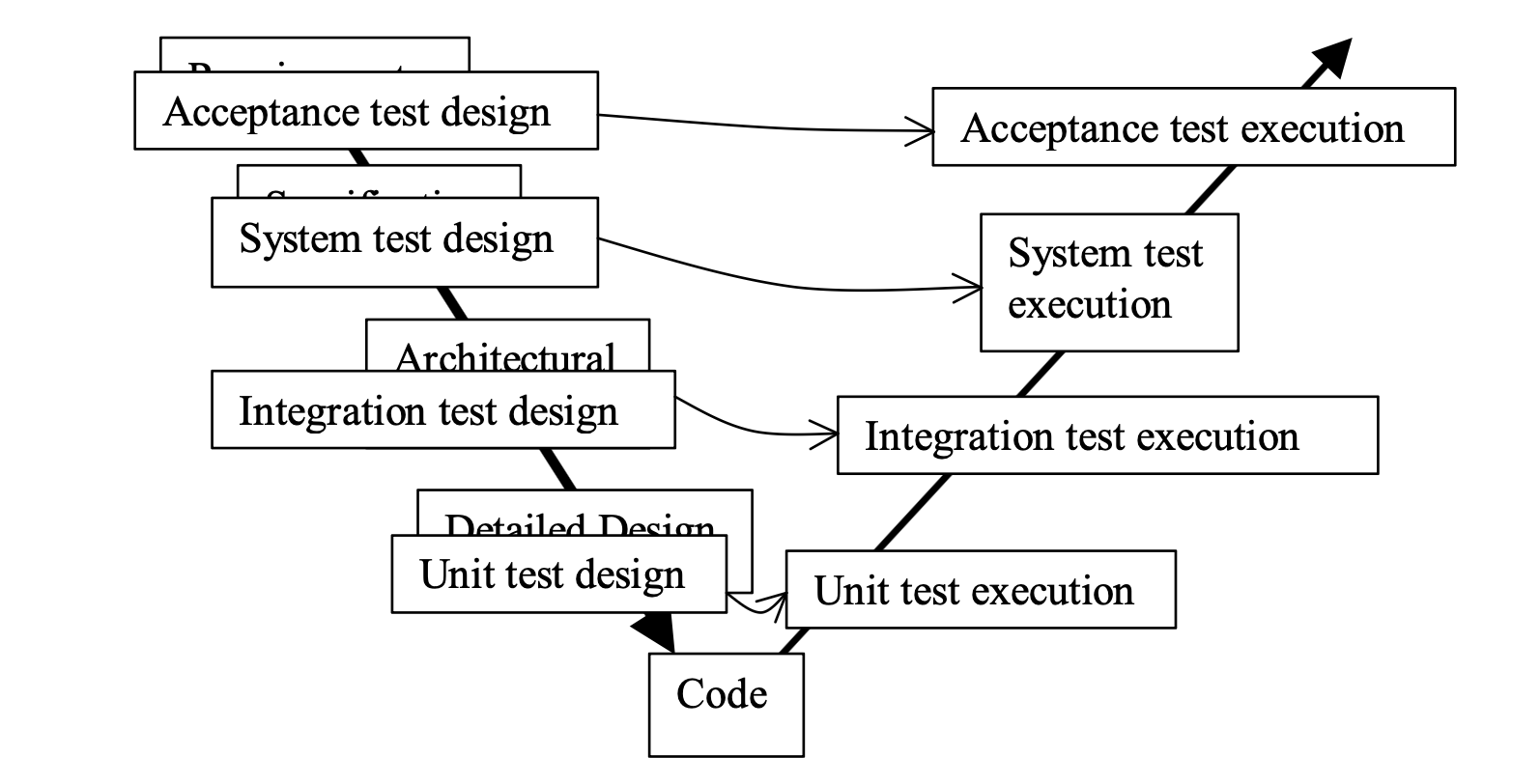

Things get more complicated if you separate test design from test execution. The latter has to be done late; the former can be done early, helping to discover bugs in the source documents.

But just because you gained testing information from a particular development phase doesn't mean it must be applied in the corresponding testing phase. You might put it off.

> "A test designed to find bugs in a particular unit might be best run with the unit in isolation, surrounded by unit-specific stubs and drivers. Or it might be tested as part as the subsystem – along with tests designed to find integration problems. Or, since a subsystem will itself need stubs and drivers to emulate connections to other subsystems, it might sometimes make sense to defer both unit and integration tests until the whole system is at least partly integrated."

Or you might advance testing. Each development phase makes prescriptions for a particular artifact (system, subsystem, unit). But you might not have to wait for the whole artifact to be finished.

> "Why not test that specification statement just after the subsystem was integrated, at the same time as tests derived from the design? If the statement’ s implementation depends on nothing outside the subsystem, why wait until the whole system is available? Wouldn’t finding the bugs earlier be cheaper?"

and so

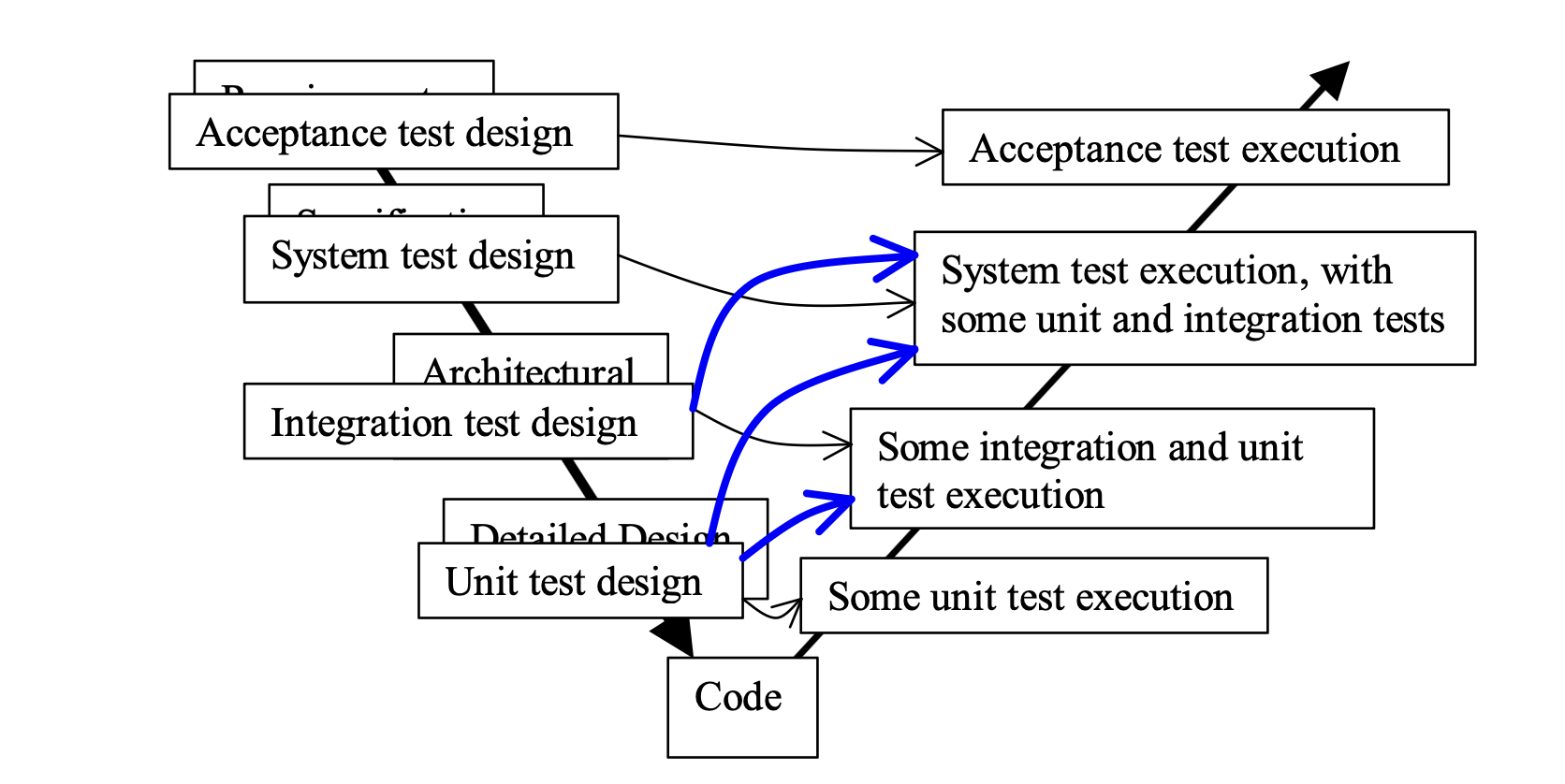

I proposed abandoning the prettily symmetrical test phases, and also ignore development phases. Rather, prescriptive statements about artifacts to be developed would be harvested whenever available and convenient. They essentially form an ever accumulating pile of "check this" commands.

The bias would be toward doing the checking as soon as an appropriate artifact was available. Essentially "just in time testing."

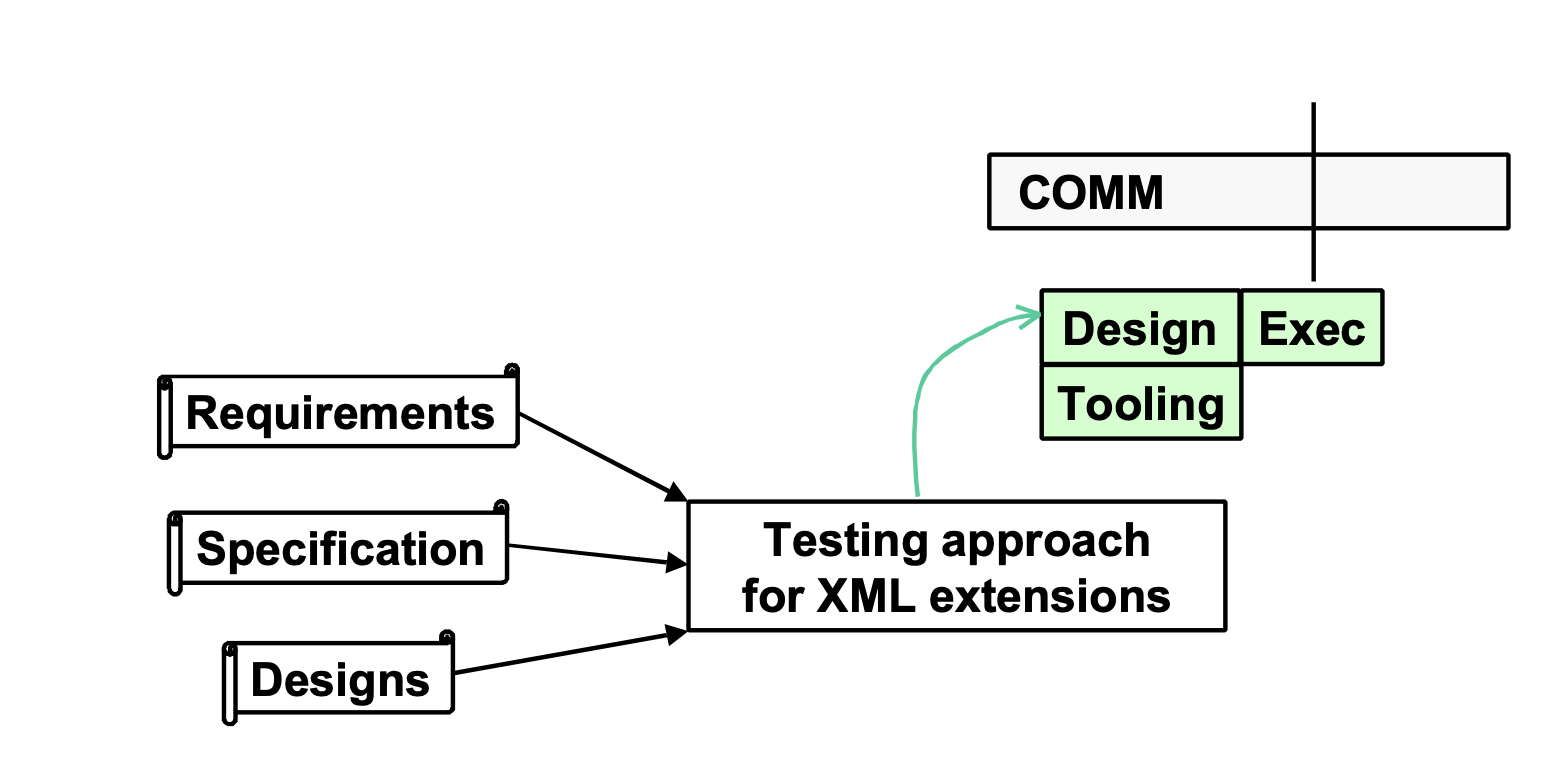

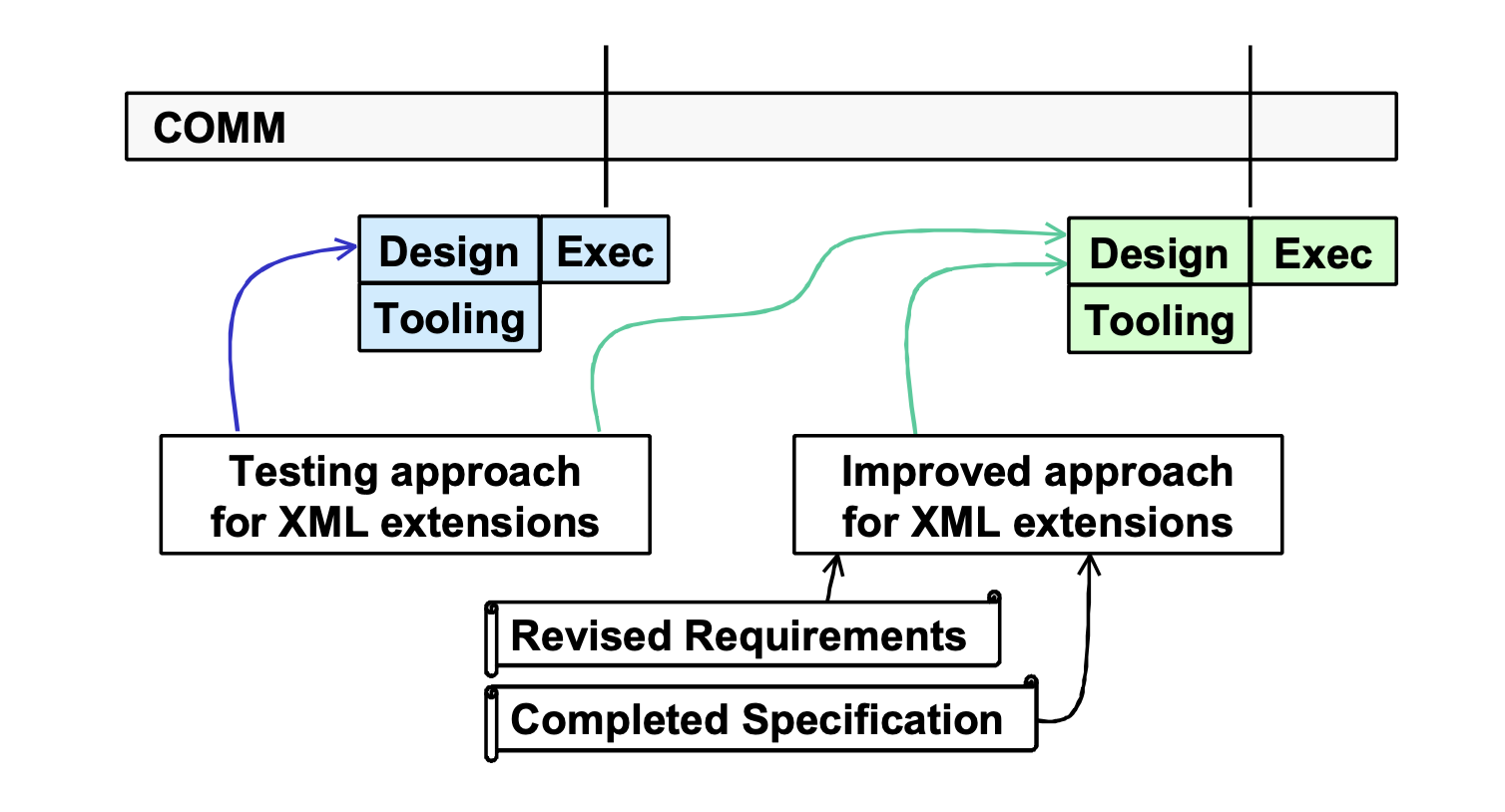

When it came to diagrams, mine looked different. I shan't explain them. Just notice how phases have given way to facts. In the waterfall model, time was implicit – the arrows are more about logical dependency than actual things finished at particular moments.

Availability, rather than logical dependency, is the organizing concept. Where dependency matters is when one team depends on stuff that will be given to it by another team.

For a particular new subsystem, we might do some of the testing right away but defer some to later, deciding based on to whom the subsystem will be released.

When it is time to design tests, information is gathered from all available and relevant sources without regard to "ontological status."

It's assumed that sources of test information are incomplete, so new information can lead to new tests. Who cares what phase we're in?

a tree falls in the forest

25-some years later, I don't remember details of how the talk and paper were received. Generally, people didn't quibble with the claims, but there were two reactions to the conclusions:

* "What you describe as inevitabilities are just because workers aren't smart enough and don't try hard enough. The solution is to fix the people, not the process."

* Apathy.

I think part of the apathy was due to learned helplessness: "Testers don't get to design development processes – our job is to do what they tell us and work around the absurdities while no one's watching, to the extent we can."

But I can't rid myself of the suspicion that:

* Those who read or listened to Royce or me fixated on the simplicity and symmetry of the starting diagrams, causing them to ignore the elaborations.

* My replacement diagrams presented an ad hoc experience. There was no core image to capture the imagination, just a bunch of descriptions of reacting to circumstances.